Nurielle Stern

- Ornamentum

- Dec 7, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 27, 2022

Medium: Ceramics

Location: Toronto, Ontario

Website: www.deepbreathely.com

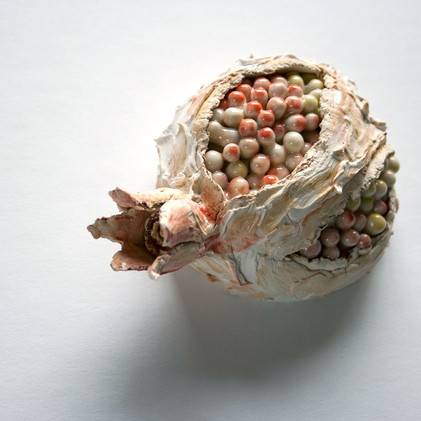

Nurielle Stern is a Toronto-based sculpture and installation artist, and a graduate of Alfred University’s MFA program in Ceramic Art. Stern’s use of ceramic materials evokes an archeological imaginary. Combining ceramics with video projection and other media, her work navigates the malleability of language and materials, and the dialectics of inside and outside—the tamed and the wilderness. She was the 2019 recipient of the Winifred Shantz Award for Ceramic Art and a 2020 recipient of the NCECA Emerging Artist Fellowship. Her work is in the collections of the Gardiner Museum, the Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery, the Schein-Joseph International Museum of Ceramic Art and others.

Your use of ceramics, from its varying scale, texture and narratives, is really unique. What drew you to ceramics as a medium?

In ceramics, anything is possible! I’m drawn to the alchemy/mad science aspect of experimenting and working with ceramics; I mix all my materials from scratch using recipes of my own devising. This allows me to make tangible a world of my own imagining, creating objects that are recognizable but have a preternatural quality to them. I often use coloured clays, so colour becomes integral to the piece instead of floating on top, like a painted object. The translucency and reflective qualities of ceramic materials also add a liveliness and luminosity to my work.

What role does material and technique play in your current practice?

I build my sculptures starting from the dust level, tailoring my clay bodies (the technical term for clay formulations) to achieve different effects. Dust is amorphous, but clay’s incredible plasticity allows me to explore expressive, and even painterly applications. I’m also adaptive in my use of non-ceramic materials, and often manipulate materials such as wood, glass, and gypsum cement as if they are clay; finding ways to make them malleable and moldable. For example, the carved wooden furniture in Whale Fall (2019), my collaborative installation with Nicholas Crombach, draws on this approach, turning an armchair frame or a rocking horse into something skeletal, bone-like, and organic.

Can you describe your process of bringing an idea to life?

I always start with an image or an atmosphere — a feeling I want to capture and bring to life with the materials. The image could be from something I read, or in rare moments of inspiration, it just pops into my head fully formed. Then I start to research the context surrounding the idea, reading lots of material in order to find threads I can follow that will lead me to new connections. Around this time I begin testing materials, methodically trying to reproduce the feeling I want to convey. There is a lot of trial and error to this part, and a lot of false starts and blind alleys in research. If I feel lost, I always return to the image/atmosphere/feeling, whichever is strongest, to guide me.

At some point in this process, connections between ideas and images begin to coalesce, adding unexpected twists, and more layers to the work, which is the ultimate goal. As an installation artist, I also always consider the site; how someone will interact with and move around an object or installation. Throughout the process, I ask myself the following questions: Will the object be confrontational, and how? Can I build in paradox, or ambiguity? What possible interpretations and impressions might a total stranger come away with? And… Is there something experientially transportive within the work, i.e. where’s the magic?

How has your practice evolved over the years? Especially over the past few years as your career has really expanded.

I have always been a risk-taker, especially in regards to working large, and pushing the materials I use to their limits. Recently I have been exploring images and ideas that have greater emotional depth, and more open-endedness in both their initial and final forms. An example of this would be my most recent installation, A Copper Nail to Kill A Tree (2021, porcelain and wood, 10 x 10 x 20 feet), in which a grouping of seven tables appear to float, supported by tree branches that emerge from each tabletop, forest-like. Each table is missing a leg, and instead sprouts one languid human arm sculpted from mint-green porcelain that in turn branches into two human hands that just touch the floor. Each table is encrusted with honeycomb forms with a honey-like glaze, and piles of rainbow-hued seashells. This piece, like much of my work, draws from historical references, and explores human relationships to the natural world. For this work, I specifically invoked and subverted art historical depictions of the passive female form. I also looked at our current and historical tendency to mythologize the natural world by drawing on Gothic literature, Romanticism, and the hybrid forms found in grotesques.

What inspires you or influences your work as an artist?

I’m interested in too many things, and one consequence is that my influences are different for every project I work on! One source of inspiration that stays constant is a fascination with the history of decorative arts and historical objects of use and value. Archaeologists look to ancient objects as a window into cultures lost in time; the craftspeople and makers of those objects were often adept storytellers in their own right, recording culturally important information in a visual language for others to interpret. Many of these objects are ceramic, especially the earliest ones as they were most likely to survive. Working in the medium of ceramics allows me to draw on this history, creating my own archaeological imaginary and my own type of visual storytelling.

Tell us about your favourite piece and why it means so much to you.

It would have to be Fable! I spent a couple of years researching a whole new way of approaching sculptural ceramic work, mixing and testing my own material formulations like a mad scientist. The installation at the Gardiner Museum spans the height of the building with fragmented reliefs that are formed from coils and ribbons of clay. Upon close viewing, the material qualities really stand out while standing back allows a cohesive image to form.

Pay it forward -- tell us about something or someone our readers should know about.

Nicholas Crombach is a sculpture artist I have been collaborating with for a few years now. We both find inspiration in historical sources such as Baroque still life painting and the decorative arts. He’s the kind of artist who can sculpt anything with ease and sensitivity, and he’s made his own foundry set-up to cast his sculptures in aluminum. We've been working together on a two-person exhibition, Petrichor, that we hope to tour with.

Comments