Jaad Kuujus (Web Exclusive)

- Ornamentum

- Jun 20, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 11, 2024

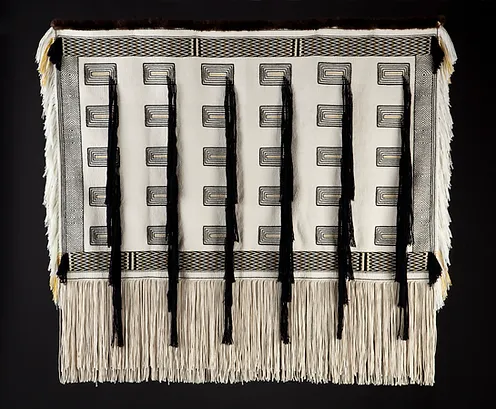

Medium/Technique: Basketry, Yeil Koowu (Raven's Tail) and Naaxiin (Chilkat) weaving

Location: Vancouver, British Columbia

1. How would you describe your art and artistic practice?

I guess I always find my motivation goes back to how I began, and how beautiful it felt to be on the land with plants I had watched develop from their small green leaves to flowers, then growing into berries. When I learned to weave cedar it was an act of devotion to the plants on the northwest coast who provide food...my interests and passions were really in nature and in the land.

2. How did you learn to weave in the traditions of basketry, Yeil Koowu (Raven's Tail) and Naaxiin (Chilkat)?

I was lucky to have teachers and was introduced and guided beyond my initial spark of interest in weaving by people who have carried this knowledge and devoted themselves to it, to mastering the techniques. I feel lucky to have worked with these teachers to learn the styles of Chilkat and Raven's Tail: Sherri Dick, Kerri Dick, William White, and Donna Cranmer.

Left to right: One Does Not Exist Without The Other, 2017, yellow cedar bark, acrylic paint. Sculpin design and painting by Jay Simeon. Image courtesy Douglas Reynolds Gallery // T'lina, 2011, merino wool, beaver fur, leather. Collection of Chief Skil Hiilans. Kenji Negai photo // She Came Up Really Fast, 2012, merino wool, cashmere, yellow cedar bark. Kenji Negai photo.

3. Where do you find inspiration for your work?

Usually I spend a lot of time before beginning a project considering what I feel the spiritual or energetic impact it might have by existing. I'm not interested in creating work for a specific market, and never want my work to be bound by the limits that presents. I work from my heart and if that isn't in alignment I don't work.

4. Can you walk us through your creative process, from initial idea to sourcing materials to the physical act of making?

For materials I use a lot of cedar bark, which involves harvesting it in the spring time. For Chilkat, it is then simmered to extract the pitch so it's easier to work with. I also use bark for basketry. Both Raven's Tail and Chilkat weaving involve a lengthly process of thigh spinning warp prior to weaving, which is a good test of one's dedication to learning in the early stages, as it can be a very long process. I then use two and three strand twining and braiding techniques of my ancestors to weave a finished piece.

5. Can you share a little bit about how you’ve used your practice – particularly Everyone Tells Me I Look Like My Mother (2020) – to challenge or question fast fashion models and ideas of disposability and value?

The inspiration for that work came from spinning mountain goat wool, a fibre and animal that was regarded as sacred by our people on the northwest coast. I spent a year relearning the way of processing yarn from the hide of the mountain goat basically, and in that time two works were envisioned to go together. One was Sky Blanket: a contemporary design and materials (merino wool/cashmere) in the shape of a traditional robe, and then a white T-shirt, titled Everyone Tells Me I Look Like My Mother. I think a T-shirt is one of garments in the fashion industry that is so disposable and used to convey so many messages and advertising, so to weave one with this absolutely sacred and spiritually transformational material I had spun by hand, for me, held this power in it. I wanted the two works to be in conversation with each other and to challenge our world view and way of relating to value and objects. Like for me, the question of what makes something of value is interesting; is it the form, or the materials it is woven with? This is such an ongoing meditation for me particularly when visiting storage rooms and trying to harness these undeniably powerful energies that are carried by those pieces. It's heavy. And for me, the question of how do we bring that world back into being in this new way. I love to believe we are capable of creating something new together. Because the reality at the moment we are in, in many ways, is very sad, and can feel hopeless at times. I think in our own ways we find ways to process and give of ourselves and this has been my way to both do this and honour a legacy of creating that was of my ancestors

6. You’ve incorporated various digital technologies into your practice in recent years. How has that changed your approach to creating?

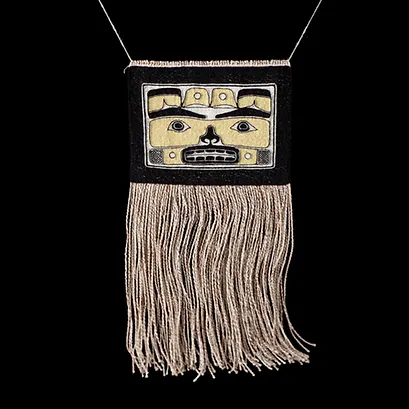

I feel like most of it happened by chance, and luckily it has always had support from people with the skills to actually handle the creation of the works, as I don't have those skills. In particular when I was working with AbTeC in Second Life, I loved the opportunity to have their help creating rooms, and basically I thought of it as a very useful tool for prototyping potential bigger works in the physical world, like installations. I mean it is so varied with the different technologies. The work that has been ongoing with Making Culture Lab at SFU has been generated out of a desire to have the works I created be more present for ceremonies, used by my family, and such...simultaneously I found as a result of that work, it presented new ways to have conversations in museum spaces around how these pieces are used, their history, and how complex that can be. In all, I think that digital technologies are another medium for stories to be told, and new ways to unravel or invite people into our traditional culture and worldview. They are also a way to engage the process of repatriation in many ways too.

7. Tell us about a favourite piece you’ve created and why it’s so memorable.

I think the piece Sky Blanket for me stands out. I was just in a particular space with a spiritual practice, and I feel that the intentions that went into that piece have lasted, and matured. It is a great feeling to see parts of yourself reflected back to you after some distance, and also out into the world.

8. Have you encountered anything particularly surprising or unexpected over your career so far?

I grew up raised by a pretty progressive dad, who basically raised me on a fishing boat and trained me and paid me the same as the other crewmen. I think being raised to see myself as equal and as capable as the men we worked with really made me take for granted that aspect. Because when I went into an art gallery, there were times trying to sell work as a woman artist, practicing a historically female art form, for the first time in my life, I felt the patriarchy in so many ways. It was the first time it really hit me that we live in a world where my work could be worth less just because of that.

9. In what ways do you hope your own practice continues to evolve?

I had a baby recently, so I just hope I can have time to get back to my practice, and eventually have it be something I can share with my daughter. I feel like it would be a great thing to be able to teach, I haven't felt that ready in my life so far, but maybe being a mom is good for me! I would really love the opportunity to execute some of those ideas generated for installation works that began in the digital world or virtual world.

Left to right: Wrapped in the Cloud, Video still. Meghann O’Brien 2018. Produced in collaboration with Conrad Sly, Hannah Turner, Reese Muntean, and Kate Hennessy. Still courtesy of the artist. // Wrapped in the Cloud in Boarder X, Art Gallery of Alberta. Photo courtesy of the artist.

10. Pay it forward -- tell us about something or someone our readers should know about.

I tend to point towards a fashion designer in Italy named Daniela Gregis. Her work is a song of our humanity, our interconnection with the plants and animals the fibres come from, and is embedded with so much respect, it is like they are prayers. I feel it represents a contemporary version of true use of all materials and no waste, and she carries forward many skills like crochet and knitting in really interesting ways. It is so many things in one I love it a lot, it's one of those things that I see someone creating from a genuine place and finding their people.

Comments